Crepes-party-hard-yolo-swag 2015

Estimated reading time: 17 minutes

Here it is! My very first game postmortem article!

In there, I will try to explain the making of Crepes-party-hard-yolo-swag 2015 (later abbreviated cphys2015), from the first prototypes to the publication of the finished product.

You can check out the project page if you don’t yet know about the game.

I don’t see many detailed functional game articles around, so I hope this will help filling that need.

You can follow the text and try the game at different stages of development by cloning the git repository,

which is available at this address.

Relevant revisions will be annotated in the paragraphs.

Use git checkout [revision] to get the game at the desired state.

Revisions to checkout are in bold later in the text.

To run the game, follow the instructions in the repository’s README file

and run this from the command line: make cairo-utils.so && csi -s crepe.scm

Use Ctrl-C in the terminal that launched the game to terminate it.

A bit of context

As stated on the project page, this game was made at the occasion of my first intern hosting, his goal was to learn about video-game designing as well as programming.

His internship lasted two months. In the first two weeks, he was mainly getting acquainted with the Scheme programming language. Since his major experience so far was with the C language, the whole functional and recursive approach was a bit foreign to him.

I taught him the very basics of the language, and made him read The Little Schemer book, from which he exercised himself a lot.

Right after that, we jumped into the core subject: video-game design.

Brainstorming

After a while, we settled on the idea of making one game a month, which we succeeded by making cphys2015 and by starting a second game.

The goal was to really publish a polished game, even if tiny and simple. That’s why we settled on the idea of a Game&Watch-like game: catching falling crepes.

As this was my intern’s first functional programming experience I resigned to only use basic functional concepts like higher-order functions, recursion and side-effect free code, for which he already had trouble coping with. This is why there is no very high-level concepts I’m usually interested in, like functional reactive programming, in this game.

In retrospect, we should probably have used these concepts. Some parts of the game’s code are somewhat clumsy.

Prototyping phase

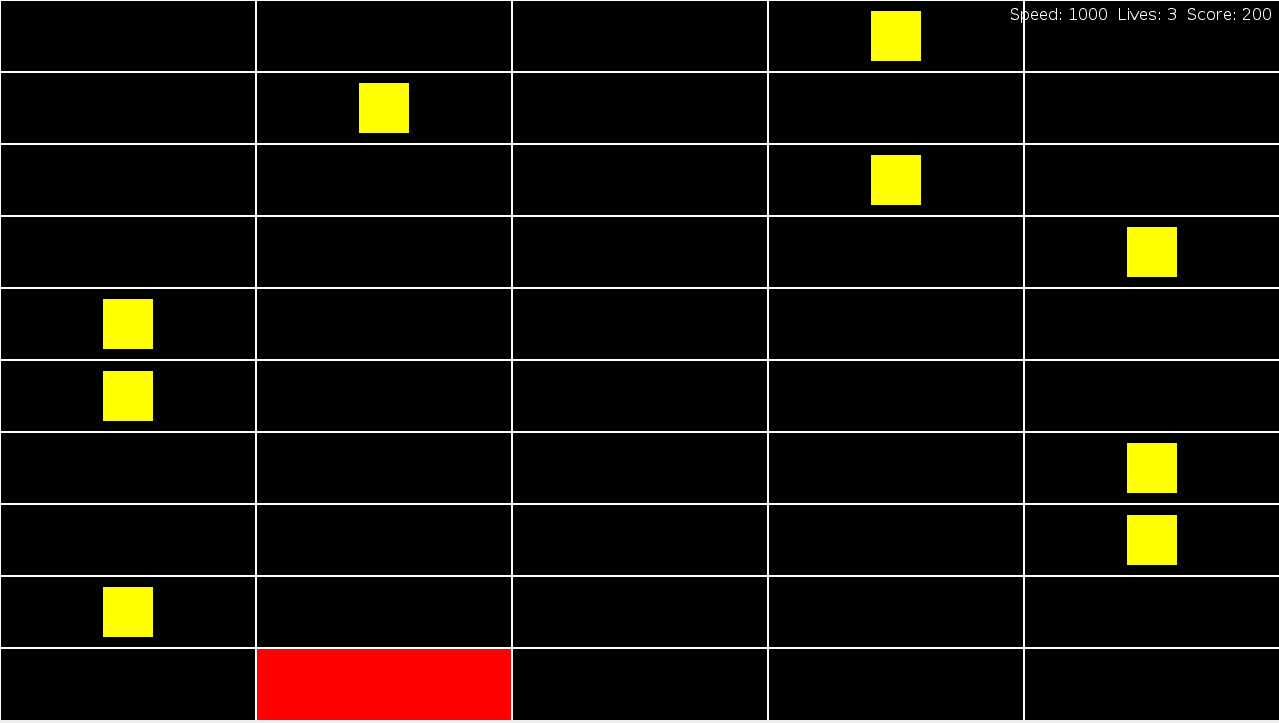

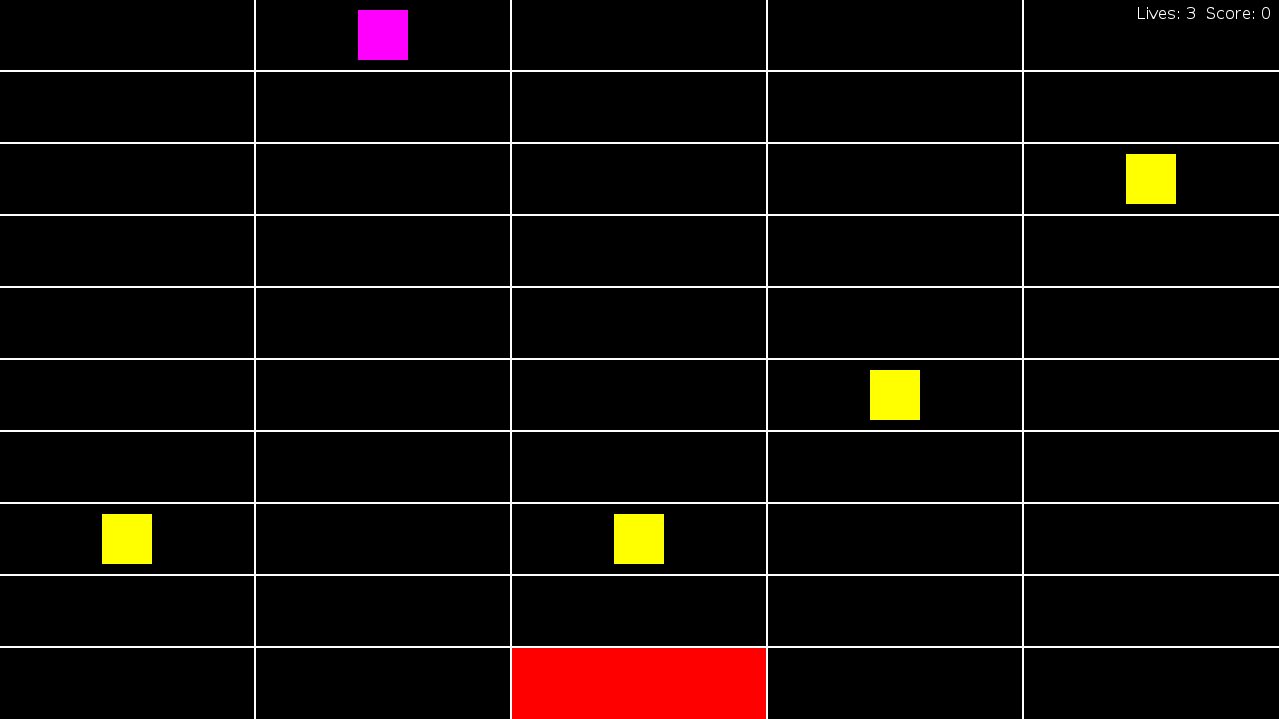

The first working prototype was closely related to the Game&Watch Oil Panic, even though we weren’t expressly looking for that at the time.

It was a simple falling blocks game, where you move your character with the arrow keys to catch the mentioned blocks (see revision v1.0~82 in the git repository).

For the graphics I used a tiny library of mine called cairo-utils, it’s just a rip off of the doodle egg’s vector graphics procedures.

We then tried a variant Reptifur (our artist) suggested: send back the crepes to the ceiling.

After a few revisions we implemented this idea. First roughly (v1.0~81) then with random speed and dropping time (v1.0~79).

We settled on that idea for the final game, as it already was quite fun.

At this point, crepes were represented as a list of the column-line position, their speed, as well as the last timestamp at which they moved, to calculate the next time they will descend.

To update the game, the code just asks the current time with get-ticks and for each crepe, checks if it should move it by comparing the current time with the crepe’s timestamp and speed. If it was time for the crepe to descend, the code would just increment its line number. A similar process happens for ascending crepes.

First refinement pass

This is where the polishing starts. We kept the latest prototype code base and implemented the different improvements on top of it.

In this first pass, we started by adding tweening in the crepes’s movements (v1.0~77).

We then added some wiggly movements to the descending crepes to somehow simulate physics effects (v1.0~74).

Next we fiddled with various details like the ascending speed, random parameters and score calculation (v1.0~70). At this point, the game’s difficulty is not tweaked at all and the game is boring.

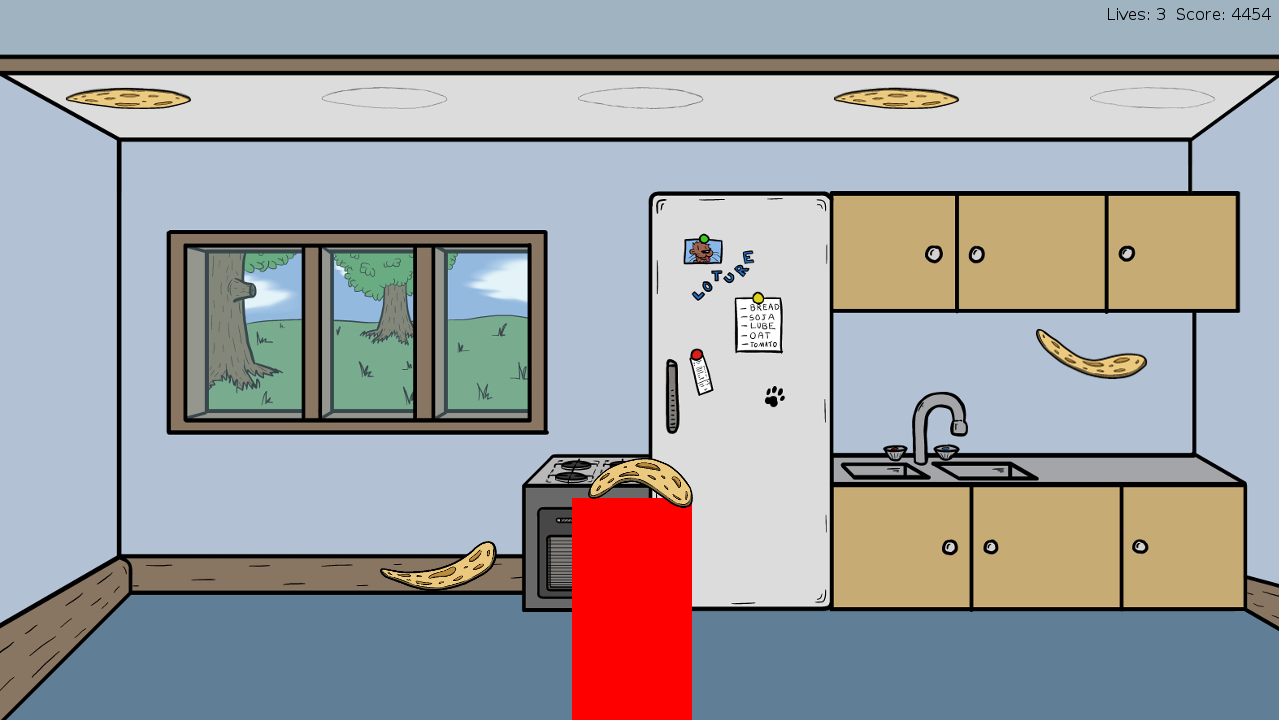

This is when our artist (Reptifur) started giving us the first revisions of the game’s graphics (v1.0~68). We quickly integrated all his contributions, animating the falling crepes (v1.0~66), adding the background image, first in black and white (v1.0~64) then with colors with some updates to the crepes graphics (v1.0~59).

From now on, you will have to execute this command to start the game:

make cairo-utils.so && csi crepe.scm -e '(start-game)'

Here is what it looked like:

Big refactoring

We arrived at the point where the code became a little bit difficult to work with so I decided to rework how everything worked.

I defined the different states the crepes can be in as three records: stick-state, ascend-state and descend-state.

I completely removed the notion of lines we previously had as well as the speed and timestamp, which got moved into the relevant state records. So from now on, the crepes are represented as a record of column number and state record.

In each state, the timestamp from the last state change is stored, which serves for pretty much every function operating on the crepes, like calculating the crepes heights or animation.

I found this way of handling game state pretty enjoyable, the state is tiny and everything can be worked out by just using that tiny bit of information.

Next I went on to implement something I wanted from the beginning of the project: self-contained builds.

In order to do that, I needed a way to first, integrate all assets into the final binary and second, to statically link with all used CHICKEN libraries.

Assets incorporation

To make that possible, I implemented a simple procedural macro, named file-blob, that takes a file name and creates a blob literal of the named file contents into the source code at expansion time. This blob is then loaded by the relevant SDL functions as an in-memory file (v1.0~57).

Here is the described macro, and one of its early use.

(define-syntax file-blob

(ir-macro-transformer

(lambda (form inject compare)

(let ((filename (cadr form)))

(with-input-from-file filename

(lambda ()

(string->blob (read-string))))))))

(define crepe-down-surface

(assert (load-img (file-blob "graph/down.png"))))

Static linking of eggs

To take care of the static linking, I first tried to reduce our number of dependencies.

In fact, cairo-utils was the less useful library we were using, since we switched to SDL for rendering images. The last use of cairo was for drawing text (score and lives), which we could do using images as well. I then removed all use of the cairo-utils library (v1.0~56).

It took me a little while to understand how to correctly statically link other libraries to my program. The first attempts (v1.0~55) were successful but pretty messy, since I did include our dependencies into our project’s repository.

Later, I removed these dependencies from the repository, but had to create tiny forks to add static object files to the build process of those.

Static linking of eggs is pretty straightforward as soon as you understand how it works.

First, we have to keep in mind how the use module loading form works.

At compile time and if the module wasn’t defined inside the source file you were trying to compile,

the compiler will try to load the import library (usually a file like library.import.so for installed eggs).

After doing so, it will translate all use of imported symbols to their corresponding symbol in the module

(for example, calling poll-event! imported from sdl2 will result to a call to the sdl2#poll-event! symbol),

these symbols are then made available at run time by loading the module shared object (like library.so).

The trick for static linking, is to use a special case of the use form in presence of compilation units.

The fact is that the use form will not try to load a shared library at run time

if the file you compile declares using a compilation unit of the same name of the module you are trying to use.

You then just need to make .o files of the libraries you use, enclose each of them in a compilation unit of the same name of the module it exports, and tell the compiler you use those units when compiling your project.

Here is a tiny example of how to do this:

;; my-module.scm

(module my-module (my-function)

(import scheme)

(define (my-function)

(display "Hello world!")

(newline)))

;; test.scm

(use my-module)

(my-function)

And how to compile it:

csc -c -J -unit my-module my-module.scm

csc -uses my-module test.scm my-module.o

To make sure your executable doesn’t depend on shared objects, you can start it with the -:d flag.

It will print this kind of lines if it still depends on shared libraries:

…

; loading ./my-module.so ...

[debug] loading compiled module `./my-module.so' (handle is 0x00000000010746a0)

…

Second polishing pass

Since we removed cairo-utils, we had to add a way to show the score and lives of the player. To that intent, Reptifur provided us with a nice hand-drawn font and a heart image (v1.0~54).

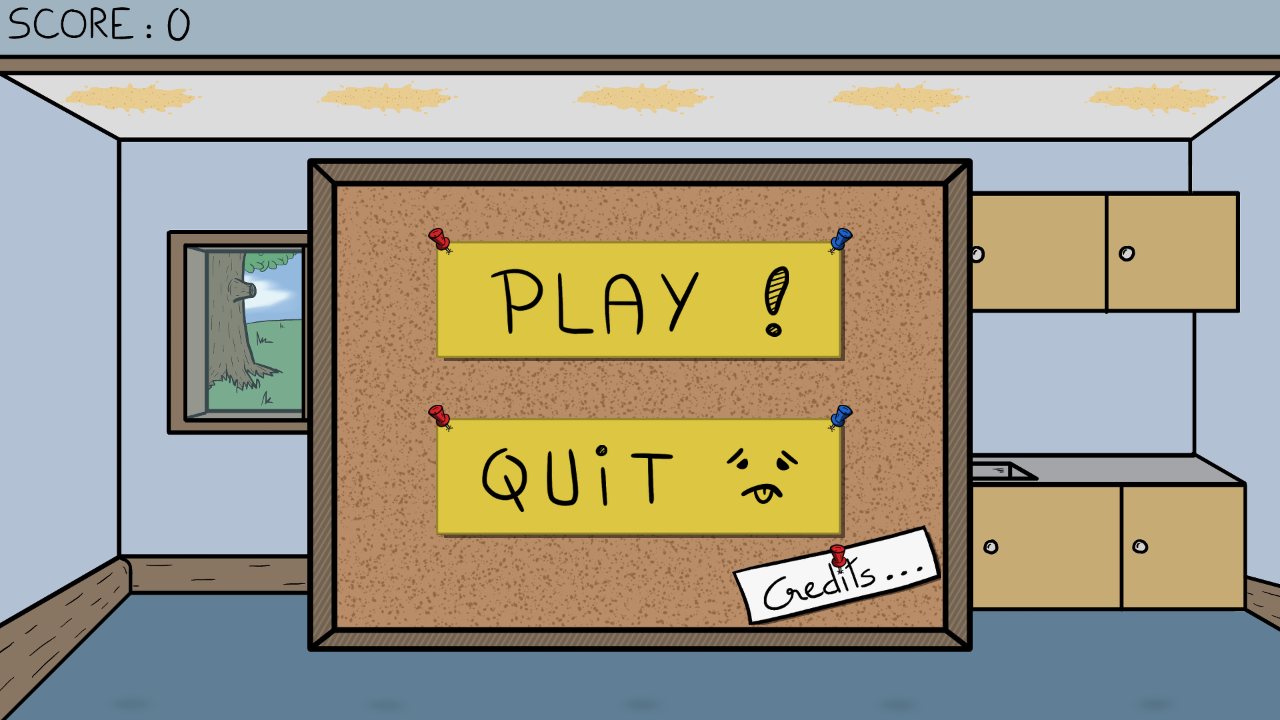

We also added a menu at this point, which was written by my intern. (v1.0~53)

Run csi resources.scm -e '(main-loop-menu #f)' to start the game from now on.

These is also where we added the first work in progress character to the game (v1.0~47).

Is this phase we also tweaked a lot of parameters and enabled violent (-O5) compiler optimizations to make sure the game was working with them.

Hardware acceleration

One other feature I wanted is taking advantage of hardware acceleration offered by GPUs. This is why I went on to the second big change of the code base: using the SDL Renderer API.

In order to achieve this, I had to fork the chicken-sdl2 project a bit further, since there was no bindings for the Renderer API at the time.

The Renderer API gave us nice advantages compared to the old method.

First, the drawing procedures became a lot faster thanks to the GPU, even though they weren’t exceptionally well designed (for example, we didn’t implement any batching or clipping).

Another huge gain was the availability of vertical synchronization, which made the game a lot less CPU hungry.

Using this API also made resolution independence very easy. With a few calls the game now automatically chooses the best display resolution available, creates a 16:9 centered (if the display is not 16:9) canvas, and scales graphics to make them fit. Scaling uses a linear interpolation algorithm when possible.

Here is the code that does pretty much all the magic:

;; Use linear interpolation for scaling if available.

(SDL_SetHint "SDL_RENDER_SCALE_QUALITY" "1")

;; Create a 16:9 window as wide as possible.

(define dm (make-display-mode))

(SDL_GetDesktopDisplayMode 0 dm)

(define win (create-window! "Crepes-party-hard-yolo-swag 2015"

'undefined 'undefined

(display-mode-w dm)

(* (quotient (display-mode-w dm)

16)

9)

'(fullscreen)))

;; Use a virtual canvas of 1920x1080.

;; This will automatically scale graphics

;; and modify mouse events and drawing coordinates

(SDL_RenderSetLogicalSize renderer 1920 1080)

Windows support

Targeting the Windows operating system was a big goal of this game development exercise, I had no knowledge of this platform prior to that, but since we chose our technologies for their portability, it was fairly easy (CHICKEN is known to work on windows, the SDL library is designed to be highly portable…).

The main hassle was setting up a cross-compiler, as I don’t own a copy of this system. The process was incredibly painless and well integrated into CHICKEN’s build system.

I just followed the steps described in the cross development section of the manual, using mingw-w64 as the target compiler.

The somewhat difficult part was to compile the chicken-sdl2 egg, as it needed different compilation options for the target system, which was achieved via the -host and -target flags of chicken-install.

To make sure everything worked, I just had to start the game in the Wine implementation of windows.

I also sent the binary to a windows user to make sure it worked on the real system.

Final polishing

Here we are then, the home stretch before release.

This final polishing phase took the longest time.

We added score displaying in the menu, otherwise the score would be pretty useless since you wouldn’t have time to read it. We also took advantage of the situation to update menu graphics, as well as to add a credits screen accessible from the menu. (1.0~28)

Start the game with csi crepe.scm -e '(menu-game-loop)' from now on.

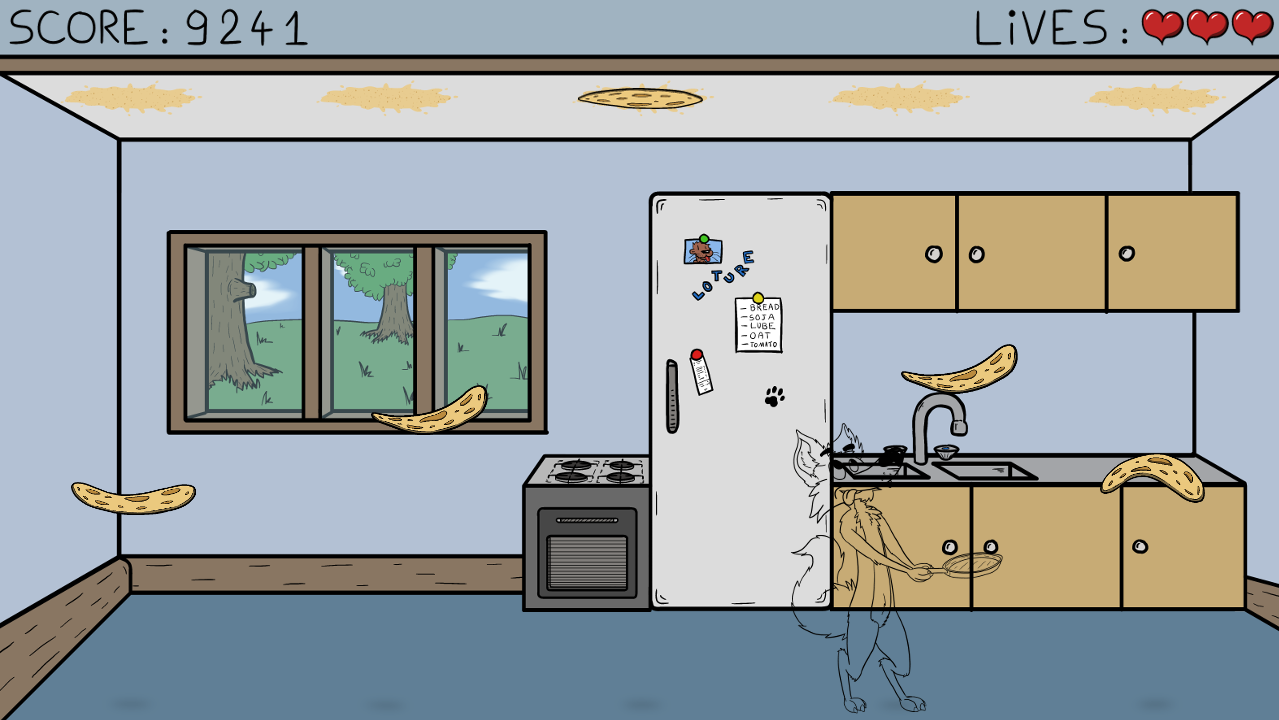

Taking care of our character was our next big step.

Our artist drew a colored version of it, made multiple faces and bodies so we could make simple animations. A little bit like Game&Watch crude animations. (v1.0~25)

The last thing we did was tweaking a few bits of code. Randomness parameters, score computation and difficulty curve were the big challenges of this phase, and probably were the hardest part of the whole development, which we probably somewhat failed according to the game’s reviews. A lot of people think the game is very hard.

For your ears only

Since we believed it was missing, we added sounds in the last few days of the development.

We did that by writing very tiny bindings to the SDL2_mixer library, and proceeded to add placeholder sounds to check whether bindings were working (v1.0~12).

We then went on to record nice sound effects, and added them to the game (v1.0~7).

Reptifur and I made three little pieces of music, which were also added to the game (v1.0).

Release

With the sounds and music in place, we could finally release the game!

I built self-contained binaries for the windows and linux platforms using the method described earlier.

Unfortunately I didn’t have access to a Mac OS computer and didn’t have a cross-compiler for that platform either. Hopefully a friend of mine, Hiro, made a build for that platform without too much trouble.

Back to the future

This whole experience of making a game with CHICKEN was really pleasant.

I didn’t bump into any language or tooling problem, which made the experience really smooth.

I will surely continue making games with CHICKEN and will probably try to implement some nice abstractions and libraries for making games with it.

I hope you enjoyed this little game and hope you will enjoy the next ones!